By Kyra Bell-Pasht & Matt Price

We recently hosted a webinar to share our initial analysis of Canadian major banks’ net-zero plans which were released earlier this year. Our analysis focused on three areas:

- What each bank includes when measuring its financed emissions;

- Adequacy of their 2030 energy/oil and gas targets; and

- The emerging strategy banks have laid out to achieve their targets.

These are the first plans the banks have released since committing to the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) in November 2021. The NZBA commitment sets out a minimum standard and indicates how it will ratchet up over time. Banks are expected to keep improving.

Measuring banks’ financed and facilitated emissions

The NZBA calls for all operational and attributable GHG emissions from bank lending and investment portfolio emissions to be covered in a baseline measurement of financed emissions. That means the share of their clients’ Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions (where material) for which the bank shares responsibility via its lending and investment activities.

When referring to investment here, we are not referring to asset management (which is covered by alternative net-zero frameworks), but rather investment banking activities, which includes helping companies raise capital by underwriting the issuance of stocks and bonds or acquiring companies through mergers and acquisitions. These are sometimes called “facilitated” emissions.

The NZBA clarifies that eventually all attributable lending and investing emissions will be covered, but for now, banks are only required to cover on-balance sheet activities, such as outstanding loans. All of Canada’s major banks have now joined the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) that provides a methodology for measuring financed emissions.

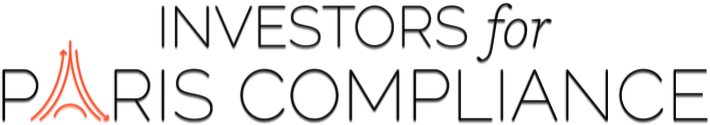

Table 1 summarizes what financed activities Canada’s major banks include in their measurement. The majority only account for on-balance sheet outstanding loans. TD and CIBC include emissions associated with some of their off-balance activities, namely, fully committed loan amounts as well as underwriting activities. Scotiabank includes fully committed amounts only for their oil and gas portfolio.

In a seeming violation of its NZBA commitment, RBC does not include Scope 3 emissions in its measurement, which results in a significant under-reporting of its financed emissions.

When assessing the credibility of a bank’s net-zero plan it is critical for shareholders to understand what percentage of the bank’s activities are covered, and if it is not all of them, then a timeline for when all attributable emissions will be covered and added to their overall measurement.

We acknowledge that this work is not easy, and the banks have taken large steps in the past year. However, at the end of the day, ensuring all attributable emissions are addressed is critical for the production of a comprehensive number against which shareholders can assess progress.

2030 energy/oil and gas targets

As part of their NZBA commitment, members agreed to set:

- Science-based 2030 targets,

- That capture Scope 3 emissions (where material),

- For their most carbon-intensive portfolios (further sectors will be captured in time).

We focus on the energy/oil and gas portfolios as a case study for best practices and to highlight the issues we see among the banks.

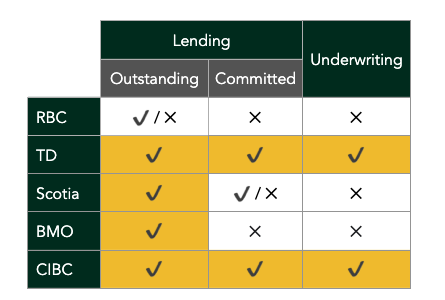

First, there is variability in what oil and gas activities banks include within the portfolio (see Table 2). TD includes coal, and calls it an “energy” portfolio. The others don’t, and refer to the portfolio as “oil and gas.” RBC has chosen to wait before setting any portfolio targets. TD, BMO, and CIBC all include a Scope 3 emissions target, which represents the vast majority of the sector’s emissions. Only TD has included all aspects of the oil and gas industry: upstream, midstream, and downstream companies.

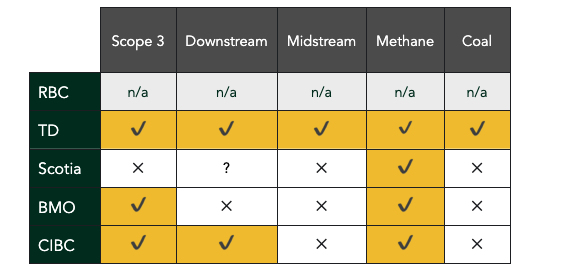

In terms of emissions reduction targets, a respected benchmark of the reductions required by 2030 can be found in the IEA Net Zero roadmap, and are summarized in Figure 1. These reductions are based on the IPCC’s 50% 1.5°C scenario, with no or limited overshoot. They are for the oil and gas industry as a whole (i.e., upstream, midstream, downstream) and include methane, which is assumed to represent 60% of the entire sector’s scope 1 and 2 emissions.

Figure 1. Absolute GHG reductions required by the oil and gas industry by 2030 from a 2019 base year (as per the IEA Net Zero by 2050 report, May 2021). Note: methane is assumed to represent 60% of the industry’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions.

These reductions would need to be increased if the portfolio included coal (which needs to reduce faster due to its carbon-intensity), or simply upstream oil and gas companies (which have a higher share of methane, which also needs to reduce faster due to its potent global warming potential in the short-term). Similarly, the target would need to be higher if the bank wanted to ensure a likely chance of reducing global warming to 1.5°C or to minimize misalignment with the UN Global Sustainable Development Goals.

Importantly, the IEA also found that no new fossil fuel development is needed in a net zero pathway – we already have enough fossil fuels in development to exceed our climate targets.

Unfortunately, the major Canadian banks have not set 2030 oil and gas targets consistent with a net-zero pathway, largely because they have set “intensity-based” targets that seek reductions per unit of production or dollar value, rather than absolute targets that ensure overall reductions. With intensity targets, emissions can rise as production rises. BMO is the only bank that set an absolute target for Scope 3 emissions. This is commendable, though it falls below the IEA threshold of -29% from a 2019 base year.

And, none of the major Canadian banks have committed to ending financing for new fossil fuels, which means they remain open to making the climate crisis worse.

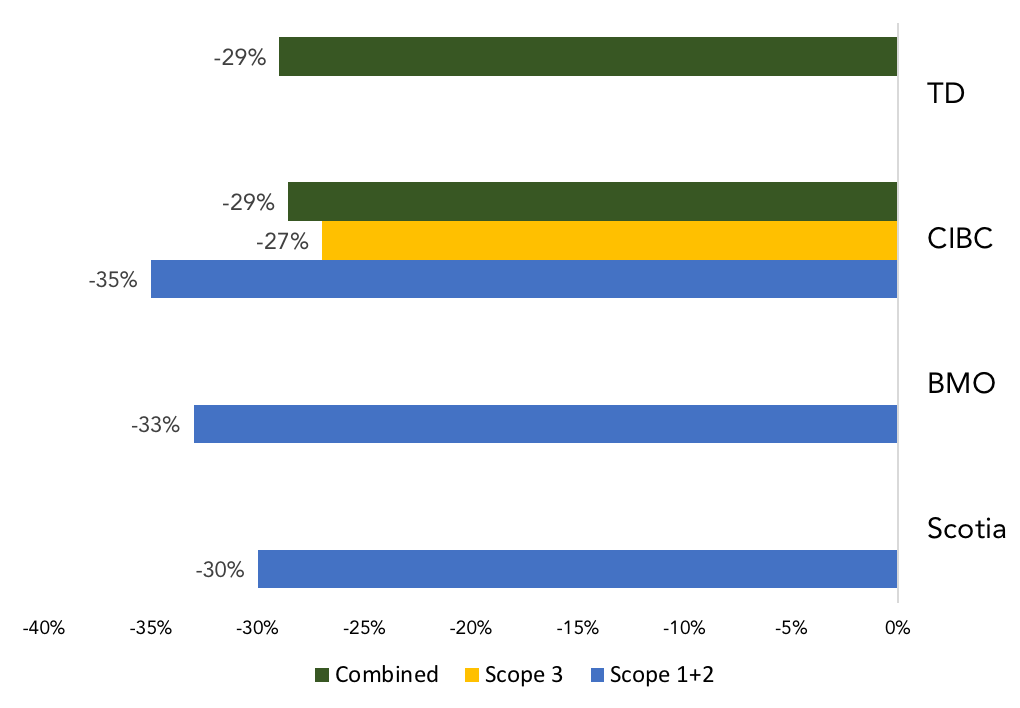

Figure 2 summarizes the intensity targets that four of the banks set for their energy/ oil and gas portfolios – again RBC has chosen to delay. These targets use different intensity metrics and a mix of 2019 and 2020 base years. It is good to see higher targets set for Scope 1 and 2 emissions as required by the IEA, but none meet the threshold set in the IEA report.

Figure 2. CO2e intensity reduction by 2030 (from 2019/2020). Note: The TD target is based on gCO2e/CAD$, while the others are based on t CO2e /MJ.

For an investor to be able to assess the adequacy of a bank’s 2030 energy/oil and gas portfolio target, it would need to:

- Be an absolute reduction target,

- That applies to the entire sector, and

- Clearly aligns or converges with a well respected 1.5°C scenario, such as the IEA’s Net-Zero roadmap.

Strategy

The NZBA requires that net-zero plans include reporting on “progress against a board-level reviewed transition strategy setting out proposed actions and climate-related sectoral policies.” At its most basic, a good strategy lays out actions with an associated estimate of emissions reductions. It’s early days, but currently none of Canada’s banks are doing this.

In broad strokes, there are at least 5 strategies that banks can deploy:

- Working with clients. Each bank says it will “work with” or “partner” or “engage” clients on their energy transition, but to date this is a black box. None of the banks have published how they will evaluate the credibility of client’s plans nor committed to disclosure on client progress.

- Sustainable finance. Each bank has made a commitment to “sustainable finance” in the tens or hundreds of billions, but none has attempted to demonstrate how – or by how much – this will reduce financed emissions. Worse, we have found examples of “sustainable finance” going to activities that increase emissions. Again, this strategy suffers from lack of definition and disclosure.

- Public policy advocacy. Banks can play a constructive role lobbying governments to implement supportive net-zero policies. Unfortunately, Canada’s major banks have a history of lobbying for fossil fuel expansion which runs counter to net zero, for example see RBC’s recent report advocating for increased Canadian fossil fuel production.

- Sectoral policies. Global banks have introduced a variety of sectoral policies that reduce or eliminate banking activity to high-carbon sectors such as coal or unconventional oil. To date, Canada’s banks have only adopted weak restrictions on coal and on oil activity in the Arctic.

- Portfolio realignment. Ultimately, some clients will not make the energy transition. Many oil and gas companies, for example, are doubling down on fossil fuels, and if they remain clients long term, then banks will not meet their reductions targets. RBC and BMO have made initial statements that they would be prepared to make the ‘necessary decisions’ to walk away from clients, while Scotiabank has argued against dropping clients.

To date, Canada’s major banks are talking mostly about strategies 1-3 above, but with insufficient detail and no attempt to quantify their impact. If the banks are to meet even the insufficient targets they have laid out to date, they will need to further develop their reduction strategies.

Conclusion

Based on what we’ve seen in this first iteration of net-zero financed emission plans, Canada’s major banks have an obligation in the coming year to bring themselves up to minimum standards by:

- Covering all attributable emissions in measuring their financed and facilitated emissions;

- Setting targets that cover entire sectors that clearly align with science; and

- Developing robust strategies that lay out clear actions with a quantification of associated emissions reductions.